How Can We Make Blood Donation Safer? The Nucleic Acid Test May Hold The Key

By: Putri Permata Sari, Muhammad Ryznar Faisal Nur Luqmani, Zelfia Riyelly

What’s this about?

Every year, on June 14, countries worldwide commemorate World Blood Donor Day (WBDD), which was initiated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2004. This event aims to express gratitude to the millions of voluntary blood donors and to raise awareness about the importance of sustainable blood donation in achieving universal access to safe blood transfusions. Blood donation plays a vital role in ensuring the availability of blood and its components, which are often essential for saving the lives of patients in critical need. Blood is frequently required for surgical procedures, trauma care, cancer treatment, and the management of chronic conditions such as severe anemia. While the act of donating blood provides significant life-saving benefits, the most crucial factor remains the safety of the blood itself. To prevent the transmission of blood-borne infections, such as HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), Hepatitis B (HBV), Hepatitis C (HCV), and Syphilis, rigorous and accurate screening procedures are essential.

In this edition, we spotlight a key issue in blood transfusion safety: the limitations of conventional serological screening and the growing potential of nucleic acid testing (NAT) to detect hidden blood-borne infections, as highlighted in a study by Nedio Mabunda et al.

How was the study conducted?

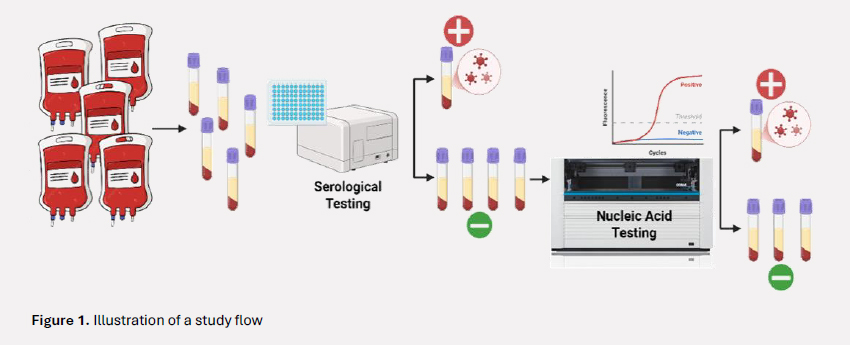

The study was conducted at two major hospitals in Mozambique between November 2014 and October 2015. It employed a cross-sectional design to assess the prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV among blood donors who had passed routine donor screening. All participants were initially screened using national standard serological assays: HIV Ag-Ab ELISA for HIV, HBsAg ELISA for hepatitis B, and Anti-HCV ELISA for hepatitis C. Donors with non-reactive serological results were then further tested using NAT with the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan system to detect HIV RNA (ribonucleic acid), HBV DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), and HCV RNA. Plasma samples from six individual donors with non-reactive serological results were pooled for testing. If a pool yielded a positive result, each donor sample in the pool was individually retested to identify the specific infection.

What did the study find?

Among all 2,783 donors, the initial serological testing revealed a prevalence of 4.6% for HIV, 4.5% for HBV, and 0.4% for HCV. However, when 2,498 seronegative samples were further tested using NAT, it detected HIV RNA in 7 donors (2.6 per 1,000), HBV DNA in 33 donors (12.5 per 1,000), and HCV RNA in 6 donors (2.6 per 1,000). In total, NAT uncovered 46 hidden infections in donors who had been cleared through standard screening methods. Notably, a large proportion of the NAT-positive HBV cases were classified as occult hepatitis B infection, defined by the presence of HBV DNA without detectable HBsAg. The estimated prevalence of undetectable infections identified by NAT was 17.2 per 1,000 donors, substantially exceeding the <1% threshold recommended by WHO for safe blood donation.

Why does this matter?

The study’s findings are significant not only because of its large and representative sample size from Mozambique, but also because they reveal a critical gap in current blood donor screening practices. The detection of hidden infections in donors who had already passed standard serological screening highlights the limitations of relying solely on conventional methods, particularly in regions with a high burden of blood-borne infections. Furthermore, the risk in this study was assessed at the donor level. However, a single blood donation is often separated into multiple components, such as plasma, platelets, and red blood cells, each potentially administered to different recipients, thereby multiplying the potential transmission risk. The study provides important insights into the need for increased awareness and the adoption of NAT to improve blood safety. NAT shortens the diagnostic window period and can identify early-stage and occult infections that serology may miss.

Any limitations?

Despite its strengths, the study does not fully explore the operational and financial challenges of implementing NAT in routine blood screening, particularly in low-resource settings.

The study was also conducted in well-equipped urban hospitals, which may not reflect conditions in more remote or under-resourced blood centers that rely heavily on rapid diagnostic tests with lower sensitivity.

What’s next?

This study underscores the need to reassess blood screening strategies in settings with a high prevalence of blood-borne infections. In Mozambique, future directions may include expanding the use of NAT beyond national reference centers, assessing the cost-effectiveness, and strengthening systems for monitoring transfusion-transmitted infections in recipients.

In the context of Indonesia, where the prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV remains relatively high in many areas, these findings highlight the relevance of adopting NAT as part of a broader strategy to enhance blood safety. The growing demand for blood transfusions across various clinical settings underscores the importance of accurately and early detecting infectious agents in donated blood. Implementing NAT in Indonesia is feasible, but it is not without challenges. Compared to ELISA or rapid tests, NAT involves significantly higher costs and requires specialized laboratory infrastructure, which is currently limited to major hospitals and central laboratories. Trained personnel and robust quality assurance systems are also essential to ensure reliable results.

Using NAT for blood donor screening can be a valuable option, particularly in line with the WHO recommendation to implement NAT in high-prevalence areas of transfusion-transmissible infections. In the long term, the use of NAT is expected to help reduce the risk of blood-borne infectious diseases through transfusion, contributing to safer healthcare practices. In the spirit of the 2005 WBDD theme: “Give blood, give hope – to-gether we save lives”, this article underscores the vital importance of ensuring that every unit of donated blood is not only available, but also safe. Safe blood saves lives—not only in emergency situations, but also by preventing long-term harm from blood-borne infections.

Article source:

Mabunda N, Augusto O, Zicai AF, et al. Nucleic acid testing identifies high prevalence of blood-borne viruses among approved blood donors in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2022 Apr 28;17(4):e0267472.

References:

- World Health Organization. World Blood Donor Day [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; [cited 2025 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-blood-donor-day

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indo-nesia. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia No. 19 Tahun 2015 tentang Standar Pelayanan Transfusi Darah. Jakarta: Kementerian Kesehatan RI; 2015.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for prevention of transfusion-transmitted infections and management of reactive blood donors [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/indonesia/news/publications/other-documents/guidelines-for-prevention-of-transfusion-transmitted-infections-and-management-of-reactive-blood-donors.

Most Commented