FROM VIRUS TO MIND: UNDERSTANDING THE CONNECTION BETWEEN VIRAL INFECTIONS AND MENTAL HEALTH

By: Rifaa’ah Rosyiidah, Adhella Menur

Mental health significantly influences our well-being, productivity, relationships, and overall quality of life. As one of the leading causes of global disability, mental disorders have seen a substantial rise in prevalence, from 654.8 million cases in 1990 to 970.1 million in 2019, as per the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study. Depression and anxiety are major contributors, while disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, though less common, profoundly affect individuals and families.

Mental disorders arise from genetic, environmental, personality, and biological factors, including changes in specific brain structures. Although it might seem unrelated, researchers are exploring how infectious diseases affect mental health. Viral infections are now believed to play important roles in mental disorders. From general complaints of feeling blue during flu to historic observations, such as the 1918 H1N1 influenza virus pandemic, where a notable increase of about 30% in psychosis and depression was recorded among survivors. Similar patterns emerged during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, with survivors experiencing higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than the general population. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of depression increased by about 27.6%, and anxiety increased by about 25.6% in 2020 compared to the previous period. These observations connect the dots from viral infections to our minds.

Research into various viruses, including influenza, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and SARS-CoV-2, has shed light on their impacts on mental health, particularly in relation to the limbic sys-tem—this network of brain regions, which includes the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, is crucial for regulating emotions, behavior, motiva-tion, and memory. Understanding these connections can help improve treatments and develop strategies to prevent mental health issues. This edition will discuss theories connecting viral infections to mental disorders, explore specific examples of viral infections related to mental disorders, and suggest future directions.

Mechanisms behind the connection

Viral infections can contribute to mental disorders through several mechanisms. Some viruses directly infect and damage brain cells (neurons), while others trigger immune responses that disrupt brain function. Some viruses can persist in the brain long-term, subtly altering neural networks. Several biological and psychological mechanisms are as follows:

Impact on brain development during pregnancy

Prenatal exposure to certain viral infections has been implicated in altering brain development trajectories. The second trimester of pregnancy is particularly critical as it is a time when the fetal brain undergoes extensive growth and differentiation, making it vulnerable to disruptions. This disruption can be mediated by direct viral effects on the fetal brain if the virus manages to cross the placenta. Additionally, maternal immune activation, characterized by transferring immune products like cytokines from the infected mother to the fetus, can further impact development. These significantly heighten the risk of developing psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) later in life.

Direct viral invasion of the brain

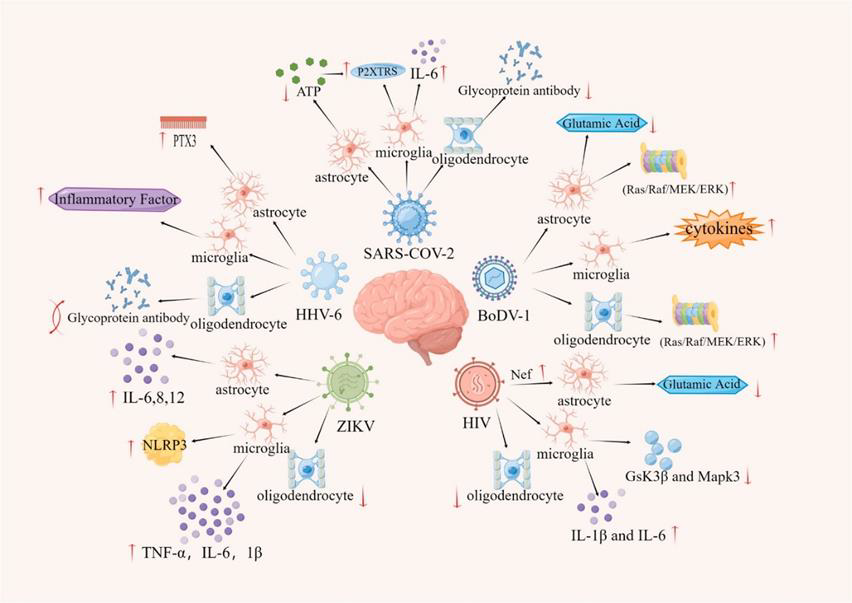

Viruses can reach the brain through hematogenous spread, entering the bloodstream to cross the blood-brain barrier, or neural spread (e.g., HSV, CMV, Zika virus, and Borna disease virus-1), which travels along peripheral nerves to the brain. These invasions can damage neurons or crucial brain-supporting cells known as glial cells, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. Damage to these cells can disrupt neurotransmitter systems and neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize itself), leading to behavioral abnormalities and neuroinflammation associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms. For example, Figure 1 illustrates how certain viral infections affect glial cells, contributing to depression.

Viral infections can have profound effects on the brain’s glial cells, disrupting their essential functions and contributing to depression. Astrocytes, essential for regulating neurotransmitters and maintaining neural balance, can be impaired by viruses, leading to disrupted signaling and increased neuroinflammation that exacerbates depressive symptoms. Oligodendrocytes, which form the myelin sheath, may also be damaged, impairing signal transmission and causing structural brain changes associated with depression. Additionally, viral infections can activate microglia to a pro-inflammatory state, releasing cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α that further drive neuroinflammation. This prolonged activation disrupts synaptic function and contributes to neurodegeneration, deepening the link between viral infections and depressive disorders. These mechanisms highlight the complex interplay between viral infections and neurobiological changes that predispose individuals to depression.

Indirect impact via inflammation and cytokine imbalance

Inflammation is now widely recognized as a potential contributor to mental disorders such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. During viral infections, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γγ—either produced within the brain or entering from the bloodstream—can impair critical brain functions such as neuroplasticity, synaptic function, and neurogenesis. Moreover, an immunopathologic event such as a cytokine storm during systemic inflammation can compromise the blood-brain barrier, intensify neuroinflammation, and result in long-term psychiatric consequences.

Researchers are also wondering why many individuals who survive sepsis—a severe response to infection—often develop mental disorders such as anxiety and PTSD. A study using animal models has pinpointed that during a specific time in sepsis, specific neurons in the central amygdala, called PKCδ+ neurons, become overly active. These neurons link to areas of the brain involved in emotion regulation, enhancing fear and anxiety circuits, which may predispose survivors to long-term mental health issues. In this study, researchers discovered that silencing these neurons during the acute phase of sepsis could prevent the development of anxiety and fear-related behaviors later on. They achieved this through two methods: genetic manipulation to turn off the neurons temporarily and administering levetiracetam (LEV), an anti-seizure medication already approved for human use.

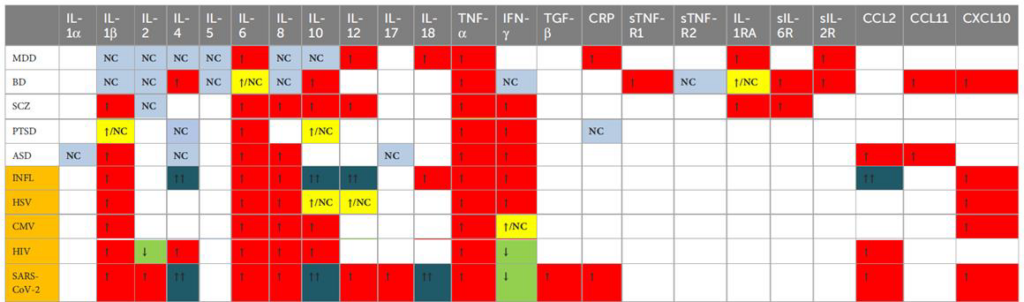

This table compares the cytokine profiles of individual mental disorders with the cytokine profiles of viral infections to facilitate the comparison of similarities or differences between them. The cytokine profile of viral infections was constructed using the same method as that of the mental disorders.

ASD = autism spectrum disorder; BD = bipolar disorder; CMV = cytomegalovirus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HSV = herpes simplex virus; INFL = influenza; MDD = major depressive disorder; NC = not changed; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; SARS-CoV-2 = Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona-virus 2; SCZ = schizophrenia; ↑ = increase; ↓ = decrease; ↑↑ = increase only in severe infections.

Gut-brain axis and microbiome disturbances

The term “gut feeling” is more than just a saying—it reflects the real connection between our gut and mental health. This link is governed by the gut-brain axis, a complex communication system that involves our gut microbiome, which significantly influences our emotions and psychological well-being. Disruptions in the gut microbiome can alter the production of essential neurotransmitters like serotonin, which is vital for regulating our mental health. Such imbalances can result in anxiety and depression. Moreover, changes in the gut microbiota can affect the vagus nerve—the direct communication pathway between the gut and the brain—impacting brain functions and potentially exacerbating neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Indirect psychological stressors

Indirect psychological stressors associated with viral infections, such as fear, stigma, and social isolation, play a significant role in exacerbating mental health issues. While not directly biological, these stressors can influence the balance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the body’s system for regulating stress hormones. This dysregulation can lead to an excessive or uncontrolled release of cortisol, adversely affecting brain function. Chronically high cortisol levels are linked to structural and functional changes in critical brain areas like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which are essential for regulating emotions and memory. A study has identified disorders of the HPA axis as a primary factor in the pathophysiology of depression.

Viruses and associated mental disorders

Influenza Virus

The connection between influenza virus infection during pregnancy and the subsequent risk of schizophrenia in offspring is one of the earliest explored connections between viral infections and mental disorders. Some epidemiological studies indicate that individuals whose mothers contracted influenza during the second trimester are at an increased risk of developing schizophrenia. This association is likely due to maternal immune activation, as the virus rarely crosses the placenta. Additionally, maternal antibodies generated in response to the virus may engage in molecular mimicry, mistakenly targeting and disrupting fetal brain proteins due to their structural similarities. These disruptions in fetal brain development can potentially lead to changes that increase the risk of schizophrenia in adulthood. Additionally, maternal influenza virus infection is associated with up to a fivefold increase in the risk of offspring developing bipolar disorder with psychotic features but not bipolar disorder without psychotic features. A study also indicated that individuals with mood disorders are more likely to have antibodies against influenza A or B viruses, with influenza B linked to a more than 2.5-fold higher risk of suicide attempts and psychotic symptoms. Further research is needed to explore these associations.

Herpes Simplex Virus and Cytomegalovirus

Both HSV and CMV are associated with several mental disorders through complex mechanisms. These include impacts from maternal infections affecting fetal brain development and from latent infections that can reactivate, causing persistent low-grade inflammation and impacting mental health. Research suggests that maternal infections with HSV and CMV may elevate the risk of schizophrenia in offspring. Additionally, elevated anti-HSV-2 IgG antibodies in maternal plasma during mid-pregnancy have been associated with a higher risk of ASD in male offspring. Exposure to HSV-2 has been shown to double the risk of depression. CMV’s influence on depression is more nuanced; higher anti-CMV antibody titers seem to increase depression risk, indicating that the intensity of the immune response might influence depressive symptoms. Furthermore, HSV is associated with cognitive disorders and may contribute to the development of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HIV significantly impacts mental health, leading to conditions like cognitive decline and depression, classified under HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). These arise from both the direct invasion of the brain by HIV and the virus’s indirect effects, such as chronic inflammation and neurodegeneration. HIV is closely associated with a high incidence of depression, primarily due to its activation of chronic immune responses that increase pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduce levels of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is crucial for neuronal health and plasticity. The virus also directly affects glial cells, such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, disrupting neural communication and exacerbating neuroinflammation, which in turn worsens depressive symptoms. Beyond depression, HIV patients are also more susceptible to psychosis, which can manifest primarily without any neurological disorders or secondarily due to opportunistic brain infections or metabolic dysfunctions. Moreover, the stigma and psychological stress associated with HIV amplify these mental health challenges, leading to isolation and heightened anxiety and depression. People living with HIV (PLWH) are also at a significantly increased risk of suicide, with a meta-analysis reporting a global suicide mortality rate for PLWH at 10.2‰, which is 100 times higher than the general population at 0.09‰.

SARS-CoV-2

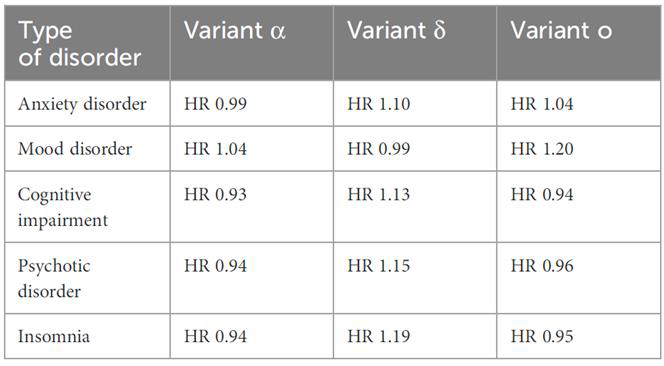

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, has been associated with mental disorders, with many individuals recovering from the infection reporting increased instances of anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairments. These issues are often associated with persistent neuroinflammation and hypoxic brain injury. SARS-CoV-2 can cause mitochondrial damage that disrupts energy metabolism, contributing to depressive symptoms. It also impacts nutritional status by reducing levels of tryptophan, essential for serotonin synthesis, thereby affecting mood regulation. Additionally, elevated levels of IL-6, a cytokine critical in the immune response to COVID-19, have been connected to schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, with some preliminary studies indicating higher levels of coronavirus antibodies in people with these mental health conditions. Moreover, the long-term effects of the virus, known as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) or “long COVID,” often manifest as chronic fatigue syndrome and brain fog, highlighting the enduring mental health implications of SARS-CoV-2. A 2022 study by Taquet et al. demonstrated that the delta variant poses a higher risk of various mental disorders compared to the alpha and omicron variants, as shown in Table 2.

Future Directions

Understanding the connection between viral infections and mental health is complex because many factors are involved. We’re left with many questions: How do different viruses, each with their own unique effects, contribute to mental health? Can we pinpoint a specific virus as the cause of a particular mental disorder? And why do only some people who get infected develop mental disorders? With ongoing advancements in neuropsychiatry and neurovirology, the possibilities for unlocking those answers are limitless.

Several key steps are essential to enhance our understanding of the connection between viral infections and mental health. Firstly, interdisciplinary research is crucial; collaboration among virologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, and immunologists is necessary to decipher the complex pathways. Future research should aim to elucidate the molecular and genetic bases of virus-induced neuroinflammation to identify potential therapeutic targets. Secondly, early detection and preventive measures are vital. Developing biomarkers to predict mental health outcomes in patients with viral infection could enable early intervention. Screening for cytokine imbalances or neuroinflammation markers in high-risk groups may facilitate timely and effective management of potential mental disorders. Thirdly, holistic treatment approaches should be integrated into viral infection treatments, addressing biological and psychological factors to enhance patient outcomes and quality of life. Pharmacological advances, such as therapies targeting neuroinflammation or specific viral pathways, promise to alleviate the mental health burdens associated with these infections. Lastly, public health policies need improvement. Public education about the potential mental health impacts of viral infections can help reduce stigma and promote timely mental health support. Integrating mental health considerations into pandemic preparedness plans, including vaccination strategies, is crucial for mitigating the mental health consequences of future crises. Let’s commit to preventing viral infections from impacting our bodies and minds!

References

- Bourhy L et al. Silencing amygdala circuits prevents sepsis-related anxiety. Brain 2022;145:1391‑1409. doi:10.1093/brain/awab475. OUP Academic

- Ji J et al. Viral infections & mental health post‑pandemic. Front Psychiatry 2024;15:1420348. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1420348. Frontiers

- Kotsiri I et al. Viral infections & schizophrenia review. Viruses 2023;15:1345. doi:10.3390/v15061345. MDPI

- Kumar D et al. Neuro‑inflammation in COVID‑19. Mol Neurobiol 2021;58:3417‑3434. doi:10.1007/s12035‑021‑02318‑9. SpringerLink

- Lorkiewicz P, Waszkiewicz N. Viral infections in mental disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024;14:1423739. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1423739. Frontiers

- Manosso LM et al. Microbiota‑gut‑brain in SARS‑CoV‑2. Cells 2021;10:1993. doi:10.3390/cells10081993. MDPI

- Pelton M et al. Suicidality in people with HIV. Gen Psychiatry 2021;34:e100247. doi:10.1136/gpsych‑2020‑100247. BMJ GPsych

- Taquet M et al. Neuro‑psychiatric risk after COVID‑19. Lancet Psychiatry 2022;9:815‑827. doi:10.1016/S2215‑0366(22)00260‑7. The Lancet

- Tomonaga K. Virus‑induced neuro‑behavioural disorders. Trends Mol Med 2004;10:71‑77. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2003.12.001.

- Yu X et al. Viral effects on neurons & depression. Cells 2023;12:1767. doi:10.3390/cells12131767. MDPI

- Psychiatric Times. The virus connection & psychiatric pathologies. Available from: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/virus-connection-how-viruses-affect-psychiatric-pathologies

- News‑Medical. Battling bugs & blues: infection and emotion. Available from: https://www.news-medical.net/health/Battling-Bugs-and-Blues-The-Interplay-of-Infection-and-Emotion.aspx

Most Commented