ENHANCING EXERCISE PERFORMANCEWITH CAFFEINE

By: Risky Dwi Rahayu

Caffeine is one of the most widely used stimulants in the world. People usually consume it in coffee, tea, soft drinks, or chocolate, but it is also added to many sports‑nutrition products such as gels, chewing gum, energy shots, and energy drinks. Research shows that, when used correctly, caffeine can improve exercise performance (its so‑called ergogenic effect).

Caffeine was first placed on the International Olympic Committee (IOC) list of banned substances in 1984 and on the World Anti‑Doping Agency (WADA) list in 2000. At that time a positive test meant a urine caffeine concentration above 15 μg mL; this limit was reduced to 12 μg mL in 1985. In 2004 caffeine was removed from the banned list, but WADA still monitors its use. Athletes are advised to keep urine caffeine below the same threshold, which is roughly equal to consuming 10 mg kg body mass over several hours—about three times the amount usually needed to enhance performance.

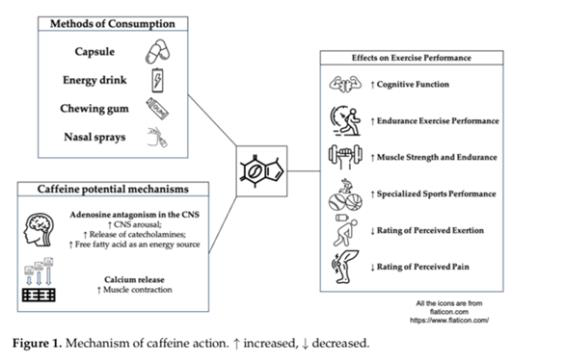

How Caffeine Works

Caffeine’s performance‑boosting effects involve several body systems. In the central nervous system it blocks adenosine receptors, reducing feelings of tiredness and increasing alertness. This blockade also raises dopamine and norepinephrine levels, which sharpen concentration and motivation while lowering the perception of effort and pain during exercise. In skeletal muscle caffeine helps release more calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which can increase the force of each contraction. Finally, in fat tissue it promotes lipoly-sis, raising blood free‑fatty‑acid levels and sparing muscle glycogen.

Peak blood caffeine appears 30–90 minutes after ingestion, and the average half‑life is about five hours. The liver enzyme CYP1A2 breaks down most of the caffeine, while 1–3 % leaves the body unchanged in urine. Regular caffeine users may develop tachyphylaxis—a short‑term reduction in some effects such as heart‑rate or blood‑pressure rise—but studies show that the performance benefits remain similar in both habitual and non-habitual users.

Most evidence supports moderate doses of 3–6 mg kg⁻¹ taken 30–60 minutes before activity. At these levels athletes typically report lower perceived exertion and fatigue, longer time to exhaustion, and better power output in time‑trial events.

Research on strength, power, and muscular endurance is less consistent, but small benefits often appear with the same 3–6 mg kg⁻¹ dose taken 30–90 minutes before training or competition. Even a one‑to‑three‑percent increase in maximal force can matter for athletes in power‑oriented sports such as powerlifting or weightlifting. Caffeine may also improve single‑sprint and intermittent‑sprint efforts, although results for repeated‑sprint performance remain mixed and need further study.

Individual Differences

Not everyone responds the same way to caffeine. Genetics—especially variations in the CYP1A2 and ADORA2A genes—training status, and habitual intake all play a role. People with the AA version of CYP1A2 (“fast metabolizers”) usually clear caffeine quickly, whereas those with AC or CC (“slow metabolizers”) may experience stronger cardiovascular effects and, in the general population, a higher risk of hypertension or heart problems with heavy coffee consumption.

Practical Guidelines

For most endurance events, the greatest benefits come from consuming 3–6 mg of caffeine per kilogram of body mass about 30–60 minutes before the start. The same dosage works for strength and power sports, while sprint or high‑intensity interval training shows more variable results but generally follows the same timing and amount.

Caffeine can be delivered in several ways. Traditional coffee or tablets remain the most common methods used in studies. Chewing gum provides faster absorption through the lining of the mouth; a dose of 200–300 mg taken immediately before or even during prolonged exercise can be particularly helpful for well‑trained athletes. Mouth rinsing with a caffeinated solution for 5–20 seconds may stimulate brain receptors and improve performance without swallowing the caffeine. Nasal sprays or inhaled powders enter the bloodstream quickly through nasal tissue, but the research base is still small. Gels, bars, and energy drinks are popular among endurance athletes, although the effects of energy drinks also come from other ingredients such as taurine.

Combining caffeine with other supplements requires care. The current evidence suggests that caffeine and creatine should be taken at separate times because a simultaneous dose does not add extra benefit and may reduce creatine effectiveness. In contrast, adding caffeine to a carbohydrate drink or gel is more ergogenic than carbohydrate alone.

Typical side‑effects include insomnia, jitteriness, a faster heartbeat, and stomach upset. Athletes should start with low doses—around 1–2 mg kg⁻¹—during training to test tolerance before using caffeine in competition.

Conclusion

Caffeine can be a useful aid for endurance, strength, and many high‑intensity activities when taken in the right amount and at the right time. Because responses vary, athletes should experiment during training, not on race day, to find their personal “sweet spot.”

References

- Guest N et al. ISSN position stand: caffeine & exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2021;18:1.

- Pickering C, Kiely J. Caffeine & exercise—what next? Sports Med 2019;49:1007‑1030.

- Pickering C, Kiely J. Habitual caffeine use in athletes. Sports Med 2019;49:833‑842.

- Wu W et al. Caffeine capsules & muscle performance: meta‑analysis. Nutrients 2024;16:1146.

- Yang C‑C et al. Caffeinated gum & exercise: review. Nu-trients 2024;16:3611.

Most Commented